By Dr. Cory Dobbs

A short, but very powerful post to share with your athletes.

How Will Your Decisions Help or Hurt Your Teammates?

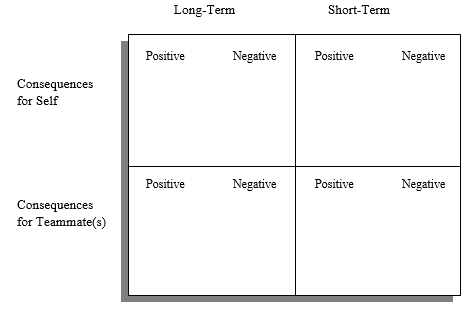

You will make better decisions if you focus on how the consequences of your actions affect your teammates. While this is only one criterion which can and should be applied to any decision you make, it is an important one. You begin by asking “What will happen to my teammate(s) if I act upon this decision? Over time, such reflective thinking will become habit.

Decision-Making

-I should act on this decision.

-I should not act on this decision.

-I cannot decide at this time (Need more information, time, etc.)

Using this matrix will not guarantee that your decisions will be good ones. However, the consideration of the consequences of a given decision in terms of one’s self and one’s teammates in the near and distant future should increase the probability that harm to relations and relationships can be avoided.

Reflection and Discussion Questions

- Do you agree with the idea that the best decisions are those that have the most positive consequences for you and your teammate? And that the poorest decisions are those that have the most negative consequences? Give an example to explain your reasoning.

- How do you know positive consequences will result from your action(s)? Inaction?

- How do you know negative consequences will result from your action(s)? Inaction?

- In which of the four quadrants would you find the most “immature” behavior? Why?

- As a team member, how can you use this matrix to help your teammates make better decisions?

About the Author

Dr. Cory Dobbs is a national expert on sport leadership and team building and is the founder of The Academy for Sport Leadership. A teacher, speaker, consultant, and writer, Dr. Dobbs has worked with professional, collegiate, and high school athletes and coaches teaching leadership as a part of the sports experience. He facilitates workshops, seminars, and consults with a wide-range of professional organizations and teams. Dr. Dobbs previously taught in the graduate colleges of business and education at Northern Arizona University, Sport Management and Leadership at Ohio University, and the Jerry Colangelo College of Sports Business at Grand Canyon University.

NEW RESOURCE

Coaching for Leadership: How to Develop a Leader in Every Locker. ($24.99)

The Academy for Sport Leadership