Coaches and athletes working together to eliminate the stigma of mental health afflictions

This post is a summary of our key takeaways from Volume 2 Episode #85 of The Educational AD Podcast, hosted by retired high school Athletic Director Jake Von Scherrer. This summary of the podcast episode is posted with permission of Coach Von Scherrer.

You can watch the 35 minute interview on YouTube at this link: Joanne P. McCallie Interview

Joanne P. McCallie is the former Head Women’s Basketball Coach at Maine, Michigan State, and Duke. Coach P’s Career Division I coaching record was 628-243.

Since retiring from coaching, Joanne’s new mission is build a foundation and to be a consultant and advocate and messenger through public speaking and writing to reduce the stigma that often surrounds the discussion on mental health.

Our hope in posting this summary of and encouraging readers to listen to or watch the podcast in it’s entirety is to inspire you to do all you can with your team, school, and community to have open discussions of the importance of being attentive to mental health and to reduce the stigma surrounding mental health issues.

She believes that post pandemic, up to 50% of our population have suffered some form of anxiety or depression. Her cause is not just about manic depression, it is about everyone’s brain health.

This is not intended to say that coaches can or should offer professional advice regarding mental health. As coaches, we need to encourage our athletes and work with parents to provide support and encouragement to our athletes to seek professional assistance when it is needed. And, to encourage all athletes to practice positive habits regarding mental health, just as we encourage positive physical health habits.

Here is a summary of our takeaways from Coach McCallie’s interview on the podcast episode:

A mental health affliction is something that and individual suffers from. It is a part of who they are, but that affliction doesn’t define them as a person. No one is “bi-polar,” it is and illness that they suffer from.

As a coach at Michigan State, she began collaborating with professionals in the field of mental health to help improve the mental health of the coaches, players, and support staff in her program. Along with sports psychologists, they worked together to spin negative perceptions that athletes have of their environment or themselves.

Administrators and coaches need to be proactive and not reactive. As much as possible, therapy needs to take place before there is a mental health emergency. Administrators and coaches should openly discuss the importance of both physical and mental health.

She motivates players differently depending on the personality and needs of each individual.

Mental health issues are diseases of despair. With mental health impairment, there’s no intention. You’re simply ambushed. You can’t defend yourself.

Unfortunately, we can’t prevent all crises that are brought on by mental health afflictions, but you can work very hard to create an environment where a young person might think twice about doing something drastic. We need to have some discussion about the subject of mental health and they know that there is somewhere to go and someone to see to get help.

Provide the opportunity and encourage anybody who has a question or concern about mental health to discuss it privately with the coach or Athletic Director. The coach can help by listening and directing the athlete to a trained mental health expert. The coach is not equipped to help the athlete in the way that the athlete needs.

The coach can still be demanding of that athlete. It does help the coach to be able to coach the individual better if you understand that they have some issues with anxiety or depression. The coach can help the athlete find a therapist because any individual with those issues should be seeing a mental health professional.

Another plus to being an advocacy for positive mental health is that If the coach understands the mental health problem, they can more effectively communicate with and collaborate with the athlete’s parents. Together they can privately come up with a plan that helps the athlete to have a more positive athletic experience. Confidentiality is extremely important.

As a young person experiencing her bipolar affliction, Joanne didn’t want to approach her parents because she felt so badly about what was happening, was ashamed, and blamed herself. She felt better with someone who was close and cared about her, but not as close as her parents. Keep in mind that your athletes may have similar feelings.

Simone Biles, Michael Phelps, and many, many others were still champions while dealing with mental health problems. Joanne was a Division I athlete and then a highly successful coach while dealing with her own mental health affliction.

We need to spread that message that mental health diagnoses do not mean that an individual cannot be successful in athletics or in any other area of life. We can still succeed in spite of these diseases. How you deal with and overcome your issues can allow you to become your best self.

Coach P’s message is that you can challenge yourself to be what you want to be and choose difficult, impactful careers without being intimidated by others or by a mental health disorder.

An example of a written message that Coach shared with one of her players: “There are no promises, but dreaming big is the way to go. Knowing full well that things may not go your way. That is the risk we assume for greatness.” This was to an elite student/athlete coming off a severe injury and working to get back to the high level of play that she was performing at prior to her injury.

Coach P did not want her to be satisfied with just coming back from the injury, but to strive to become even better than she was prior to the injury. Joanne’s purpose with the note was to redirect the athlete’s thinking and get her into a better headspace. Dreaming for the highest levels is what it is all about.

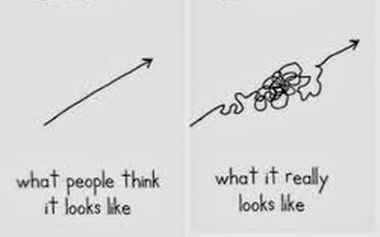

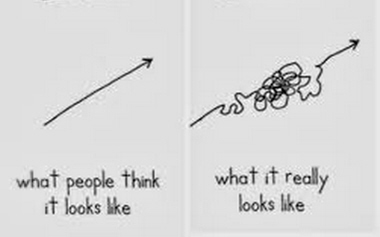

Coach McCallie does not focus on the outcome. She focuses on the process. To go after the highest levels of achievement, you have to commit to the process and commit to accepting the results that your process leads to. And, sometimes things work out, but not in the timeline that the athlete or coach has established for themselves.

Athletic Directors Toolbox segment of the show. This is a segment at the end of every episode of the podcast where the guest is asked what three things they can she share with the audience that she would put in her toolbox if she were an athletic director starting a new job.

Coach P actually gave us four items for the Athletic Director’s Toolbox 🙂

1. Get to know the people in the athletic department as individuals. They don’t work for you, you all work together.

2. Be a “coaches Athletic Director.” Support the program by giving the coach confidence.

3. Dig out the problems before the surface and support the coach.

4. Loyalty is something that can never be underestimated.

Joanne also shared her ideas of best practices for conduction practice for coaches of any sport. (In addition to creating her own success, she had the privilege to learn from coaches such as Tom Izzo, Nick Saban, and Mike Krzyzewski.

1. Every minute of practice is accounted for and planned in advance.

2. You have to practice the way you are going to play.

3.There is no room for generalities. You must be specific about what outcomes you are looking for in all areas.

4. She has a “Thought for the day” every day to share with her team.

5. Coaches must constantly ask themselves, how are we going to use our philosophy to better us in practice.

6. The players and the coaching staff must provide each other with positive energy and feed off of each other.

7. In order for your practices to have the best opportunity for individual and team improvement, the head coach must delegate duties to the assistant coaches and to the players.

8. The coaching staff must make time in practice to nurture one on one personal relationships with each student-athlete. One on one and team motivations are different and a coach must be able to effectively do both.

9. The feeling of being completely absorbed in practice is a great feeling for both coaches and athletes.

Joanne is the author of the book “Secret Warrior.” that details her journey as both a student athlete and a very successful coach who continually had to battle impaired mental health.