Editor’s Note from Brian: I believe that these 7 lessons apply in athletics when athletes are working to acquire new skills or improve existing ones as well as in academics.

How well do your students fail? Poet Samuel Beckett once said, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better.” Turns out he was sort of right, as research by psychologists over the past two decades has found that the way you explain your failures can have a profound impact on your future behaviour.

Research from sport suggests that if athletes attribute failure to permanent causes instead of temporary ones, and if they overgeneralise instead of being specific, it can lead to them feeling less confident, more anxious and performing worse in the future.

Could this be applied in schools? Students have many highs and lows over the course of the year. Failure at some stage is inevitable. Some students see their failures as permanent (“I will never be good at art” vs. “I am struggling in art at the moment”), and they overgeneralise (“I don’t like maths” vs. “I don’t like algebra”).

To combat this, some schools have started running a ‘failure week’ to help promote the importance of taking risks, learning from mistakes, and reducing students’ fear of failure. Others are incorporating these principles regularly into PHSE lessons and enrichment days.

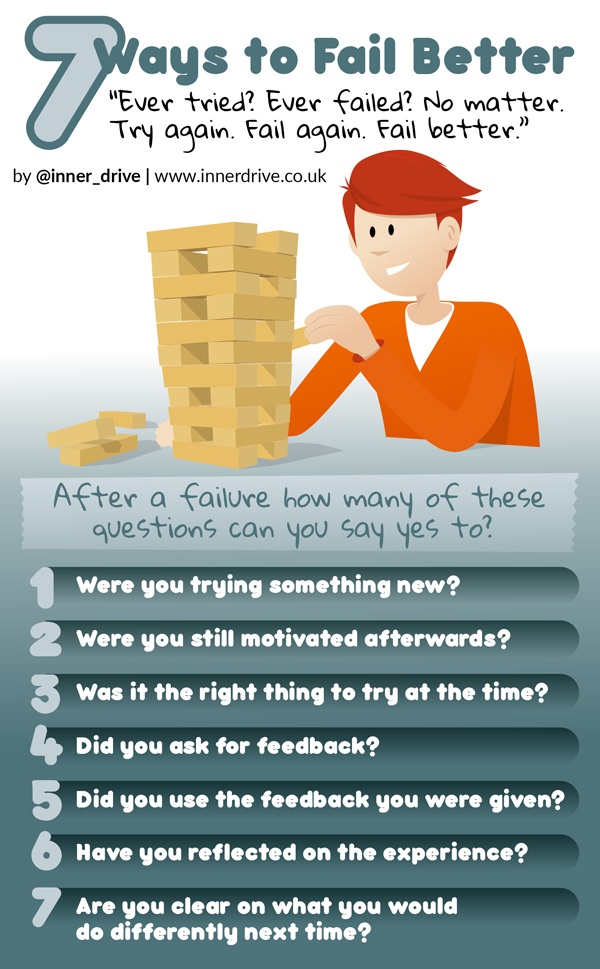

HOW TO FAIL BETTER

So how can we help students fail better? It is important to note that failing better is different from aiming to fail. The former focuses on learning and development; the latter suggests low expectations and lack of effort (which is the opposite mindset of what we promote). Students ‘fail better’ if they can answer yes to these questions…

Were they trying something new?

Being open and enthusiastic about new and challenging situations is a key characteristic of having a growth mindset. We want to help students shift away from focusing on ‘proving myself’ and more towards ‘improving myself’.

The teenage years offer a unique window of self-discovery and improving self-awareness. It can be when people discover what they are passionate about. Part of this process is trying new things, experimenting, and finding out what one’s strengths/weaknesses might be. Failures are integral to this. Helping students understand this can help aid their learning and development.

Were they still motivated after the setback?

Research on teenagers has found that those who are motivated by learning and mastering a subject, compared to those who are extrinsically motivated by rewards, display higher levels of emotional control before an exam, have higher levels of confidence, and achieve better academic performance.

Doing well at school is more akin to a marathon, rather than a sprint. Motivation needs to be robust and durable in order to aid resilience. Focusing on improvement, on learning, and on getting better should ensure that this happens.

Was it the right thing to try at the time?

It is easy for students to judge how good their decisions are based on the outcome (i.e. if it ended up well, it was a good decision; if it ended up badly, it was a bad one). This is a mistake, as sometimes the result may be down to randomness, luck, or a million other factors. This can lead to people throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Statistician Nate Silver, the only man in America who correctly predicted how each of the 50 states would vote in the 2012 Presidential election, states that instead of judging decisions based on the eventual outcome, it is far better to judge them based on the information you had at the time.

If students make the best decision possible from the information available, then perhaps the mistake was down to execution of the skill and not the thought process going into it. This is an important distinction to make, as it can help identify which part of the process to target for improvement next time.

Did they ask for feedback (and then use it)?

There is a great quote that says, “Real failure is a man who has blundered, but not cashed in on the experience.” If students are going to suffer from setbacks (and it is a certainty that they will at some stage), then there is a three-part way to ensure they learn the most from it.

First is the act of asking for feedback. This is a great behaviour to praise, as it is the behaviour you want them repeat after future failures. Second is being open to the feedback. This is a fundamental part of learning. If students feel that they are being judged or attacked, it is unlikely that they will heed the feedback, no matter how helpful. Third is getting them to action the feedback. It is not enough to have good intentions; behaviour change comes from doing, not just thinking about it.

Did they reflect on the experience and know what they would do differently?

Setbacks can aid the learning process, but only if the person experiencing it takes the time to reflect on what has happened and as a result, is clear on what they would do differently next time. Otherwise, it is likely that they will repeat the same mistakes again and again in the future. It is ok to make mistakes. To keep making the same one is criminal.

Having students ask themselves ‘what would I do differently next time?’ is a great question for two reasons. First, it stops them dwelling on the past, which can reduce student stress. Second, it gives them a sense of control over the situation, which will help boost their confidence and motivation when moving forward into the future.

FINAL THOUGHT

We all want the students we work with to be successful; however, it would be foolish to think that they will never fail. We don’t want students to fail more, but if (and when) some of them do fail, we want them to fail better. Helping them fail better isn’t negative; if anything, it may be one of the most positive skills we could teach them.

About Inner Drive

InnerDrive is a mental skills training company coveing the traditional areas of sports psychology and mindset training.

Their work covers the traditional areas of performance psychology, sports psychology and neuroscience. They work with over 120 schools in England and last year worked with over 25,000 students, teachers and parents.

The company is led by Edward Watson, a retired Army major and Bradley Busch, a HCPC registered psychologist.